Where do we go from here: The State of Play in Scottish State-school Classics

This is the transcript of a paper delivered at the Classical Association Conference in St Andrews on Friday 11th July, 2025.

Since 2014, Classical Studies – the course provided by the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) – has seemingly touched the bottom, and through sustained effort from a huge array of people and organisations, revived its fortunes somewhat. Instead of staring down the barrel of the same gun as Classical Greek – a course which was discontinued that year and thenceforward and to this day denied to state school pupils in Scotland – Classical Studies, as you will have no doubt heard from other panels and presentations, has become rather a success for ancient world studies, and is now in better health, and we can start looking to the future with, if not optimism, then perhaps with a sense that the subject can be returned to a position of stability in Scottish schools.

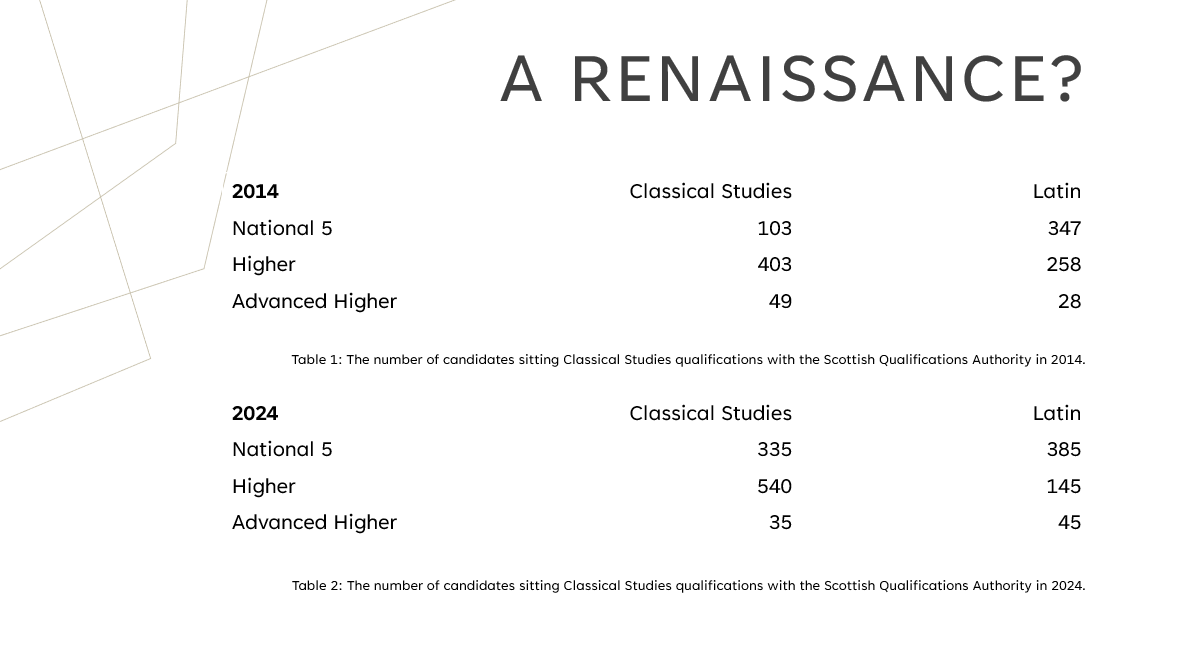

Pupil uptake numbers for Classical Studies and Latin in 2024.

A quick look at the SQA’s own statistics confirm this minor revival: in 2014 just 103 pupils sat National 5 (the certificate usually taken at the age of sixteen) Classical Studies, while in 2024 this figure had more than tripled to 335. Not gigantic numbers, but the trend is significant. Word is out in schools, and head teachers are green-lighting National 5 Classical Studies courses with greater and greater frequency. This year’s data is not yet available, but I am confident, from anecdotal evidence, that these numbers will jump again this year.

However, being a bit of a moan, and knowing the complications imposed by the educational austerity within which we work, I’m afraid I am here to suggest – and I’m sure Arlene will confirm some of this later in the panel - there are still significant structural difficulties to overcome if we are to restore Classical education in Scotland to even a tenth of what it once was.

So, let us quickly return to those SQA statistics which showed the remarkable growth of National 5 Classical Studies. They are very encouraging numbers. It is somewhat misleading, though, to take them as an indicator of the rude health of Classical Studies as a whole. Over the same decade – 2014 to 2024 – Higher Classical Studies (the course sat by pupils at 17/18 - has moved more gradually from 403 entries to 540, SLIDE but Advanced Higher (the bridging course to university study) remains in double digits; indeed, its numbers have declined. There is much to be done there.

The more obvious concern is the fate of Latin. As mentioned, the SQA withdrew Classical Greek in 2014, but the number of candidates sitting Higher Latin has crashed from 258 in that year to 145. A fall of 44%. When we factor in that 115 of those Higher Latin pupils attended private schools, we are left with the reality that in the entirety of Scotland last year just thirty state school pupils sat Higher Latin.

This points us to the key factor inhibiting the teaching of Latin in Scottish state schools – there simply are not enough teachers.

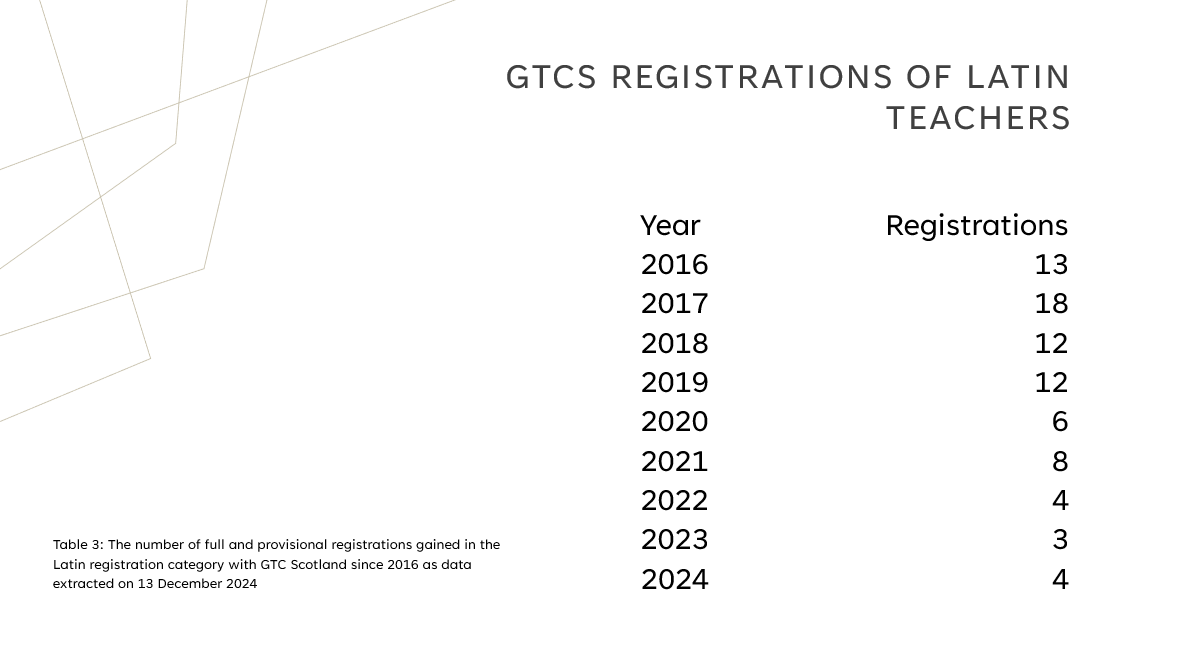

Number of teachers registering with the GTCS for Latin since 2016

While the General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS) has been registering new teachers in Latin over the last several years, these have almost exclusively been teachers from other countries, usually England, who have come to take work in Scottish private schools.

State schools have so far been able to take a “the market will decide” approach to Latin, saying that if parents do not ask for the subject, then there is no responsibility for them to provide it. There is no legislation in place to protect Latin from this kind of managed decline. We are now in the downward spiral that Latin should not be provided because parents have not asked for it, and because there is no Latin teacher in a school, parents are unlikely to ask for it, saying, “well, state schools don’t teach Latin anymore, do they.”

If the solution is to train more teachers in Latin, then where are they coming from? Certainly not state schools. And even if there were pupils qualifying in Higher Latin and then going on to take university-based Classics courses, there is no provision for teacher education in Classical subjects in Scotland at all. None. Pupils may want to become Latin teachers, but there is no training. It starts to resemble a constructive dismissal: no single party is guilty of breaching their responsibilities, but the combined effect is to make the subjects unavailable in state schools.

I myself have presented National 5 Latin candidates for the last three years, having done a Latin paper as part of my undergraduate Classical Studies degree, but achieving registration to teach Latin with the GTCS requires 80 Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF) points, while my Open University paper awarded only 60. As such, despite teaching and presenting examination candidates, I am currently unregistered in Latin. This matters, because it suggests to school leaders that the subject is less important than others.

In anticipation of this panel, I asked in the Classical Studies Collegiate Group – a Microsoft Team for state-school teachers created in 2022 – if anyone had experienced difficulties in getting registered by the GTCS either for Latin or for Classical Studies. I was not short of responses:

“When I have queried my lack of qualification in Classical Studies – SLT told me it is at the discretion of the school because some rural or remote schools in Scotland also have to do this as their teacher numbers are limited and pupils must have personalisation and choice.”

In a roundabout way, saying that GTCS registration does not matter. The GTCS, of course, take a completely opposing view, that no teacher should be teaching ANY subject to examination level without registration in that subject.

“The additional registration requirements are a deterrent to them (other colleagues) as they would need to complete additional modules of learning.”

“I have looked into doing further credits, but the cost is high for the Open University, and for me online courses would have to fit around my family life.”

“I am undertaking the Open University courses, but I do not have the paperwork for full registration yet. If the GTCS came knocking at our school, we would be able to paper over the cracks, but it is not ideal. I am the driver of the courses but if I were forced to step away for GTCS reasons that would mean the end of Classics here at my school.”

The threat is I think obvious. If the GTCS were to insist on all Classics teachers being registered, and that they should possess the 80 SCQF credits they demand for registration, we would lose dozens of state school Classics teachers overnight.

In the absence of teacher training in Scotland, we are left to find teachers from other subjects who are willing to add Classical Studies or Latin to their GTCS registration; yet even when we find teachers willing to do that, there is no clear single-shot course which they can undertake. Instead, they must independently piece together their qualification from disparate sources, and almost always under their own steam, bearing the financial costs of training themselves, and on top of their full-time workload. It is additional workload which should be compensated for within their working-time agreements in their schools, but is not.

We are quick to praise these teachers’ commitment to Classical education, but there is almost nothing by way of reward or support outside of the Classical charities. “Do it for the kids” is a mantra which school managers are prone to throw around, but it is not sustainable to ask individual teachers to bear all of this additional work. Perhaps it would be more appropriate to ask managers, schools, and local authorities to invest in Classics, to “do it for the teachers”. If teachers are the people who work with the kids day in, day out, it is surely the role of school managers and local authorities to make that job easier.

Unremunerated labour is currently the only available way to achieve registration. As a quick sidebar, it is also the case that some staff will undertake the introduction of some Classical Studies classes into their school as a means to achieving a promoted position, of demonstrating “whole-school leadership”, and then leaving the classroom, closing Classics in that school.

Keeping Classical Studies in the schools which have already introduced it is an ongoing worry.

As one respondent to my enquiry put it:

“The sustainability of the subject is a concern - it is popular, and the pupils really enjoy it, however if I or my colleague are ever off it does put strain on the department. I know other colleagues who would be willing and happy to teach the subject, but the additional registration requirements are a deterrent to them.”

Many schools have only one member of staff well-versed enough in Classical Studie to present the course, and this has very obvious problems baked-in.

“I went on maternity leave and the school were unable to secure a qualified Classical Studies teacher to take on my allocation of classes.”

One teacher replied to my mailshot thus:

“The process of bringing Classics to my school has shattered my faith in the relationship between promoted and non-promoted staff. Although I am only a classroom teacher, I carry the workload of a head of department as I am the only teacher qualified in Classical Studies. If I am off, pupils have no qualified cover, and this imposes a horrible weight of pressure and guilt on me. Managers are happy for me to shoulder all this additional workload, but they will not provide the safety net of additional staff with regard to either my health or the health of the subject.”

Getting Classical Studies through the door is a very good first step, but once it is in it has to be made sustainable. The staff delivering it must be supported in the same way as any other subject, and this is currently not the case.

Things would be easier were there some kind of orchestrated online course for interested staff, delivered by university lecturers, as a twilight CPD, free of charge for teachers looking to add Classical Studies or Latin as an additional subject. Again, though, in a world of educational austerity, schools are reluctant to spend on teachers’ CPD at all, much less to add subjects which are generally regarded as unnecessary.

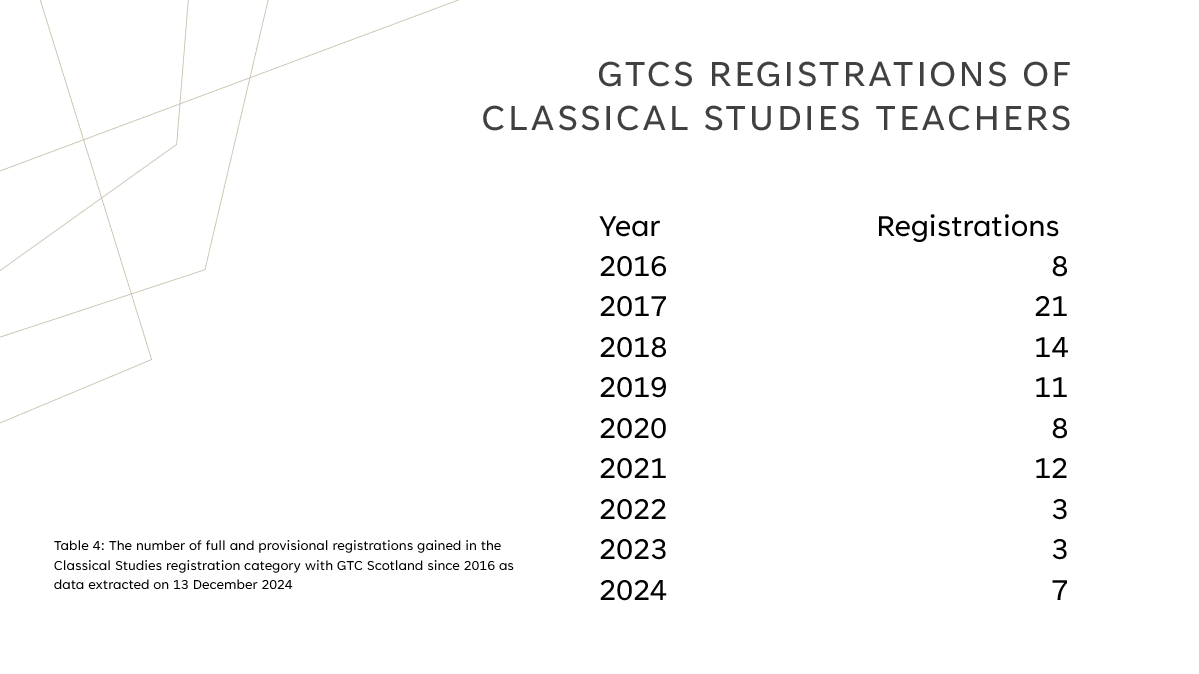

Number of teachers registering with the GTCS for Classical Studies since 2016

This is not to suggest that registration has stalled. As you can see, the GTCS continues to register new teachers in Classical Studies, and a lot of them work in state-schools. After teaching Classics in my school for six years, I achieved my own registration in 2022. But the road to registration is neither clear nor easy.

There is a deeper, and more anxiety-inducing element to all of this, and that is with regard to staff contracts. I am employed by my local authority as a teacher of English, and as such they would be within their rights to reshape my timetable for me to teach English exclusively, and close down Classical Studies and Latin. They can point to my contract and insist that it is my job, and my ten years offering Classical courses would go down the drain. After all, Classical Studies and Latin do not take on as many pupils as English, and so they are more expensive for the school to run. Other teachers, in other schools, have raised the same concern.

One local authority explained that a teacher’s contract cannot be changed, and that the only way to do so would be to create a new job, and advertise it in the usual manner. In which case, staff would have to reapply for their own job, and run the risk of not getting it. This also reduces the likelihood that a staff member would ask for their contract to reflect their actual job. It gives the authority all of the power in the dynamic and leaves the staff – and subject – on a very shoogly peg.

Consequently, we have many Classical Studies teachers working, often exclusively in Classical Studies, without a contract that reflects their working reality. If a school needs to change direction, or cut budgets, it is only too easy to insist that the terms of the original contract – in a non-Classical subject - be fulfilled, and Classics in that school would die.

Latin is a bigger and harder nut to crack because it is simply not feasible that a teacher of History, for example, could just start delivering Latin lessons. There is an imperative to have significant subject knowledge before taking a Latin class, and this is harder than picking up another subject in the same language, such as is the case for Classical Studies. Latin’s dwindling status in state schools suggests that there will be no state-school Latin teachers in Scotland when the remaining generations retire, and like Classical Greek, Latin will become a synonym for “privately schooled.”

It is my deep belief that the Scottish government is asleep at the wheel when it comes to Classical subjects. Bullet point two of their own National Improvement Framework 2025 says,

“Scottish education should be ambitious, inclusive, and supportive in order to… achieve equity: ensuring every child and young person has the same opportunity to succeed.”

Every. Child. And. Young. Person.

The. Same. Opportunity. To. Succeed.

It is beyond debate: this is not the case for Classical subjects, and for Latin in particular. State school pupils do not have the same opportunity to study, and succeed, in Latin, and it very much depends on your postcode as to whether you will have the same opportunity in Classical Studies. For decades, using reverse snobbery around Classics, successive Scottish governments have been able to turn a blind eye to the decline in access to Classics for state school pupils. But this is a canary in the coalmine, and our colleagues in modern foreign languages are starting to see similar problems emerge. They, however, are somewhat protected by legislation which makes the provision of modern foreign languages compulsory, even though pupil uptake numbers are now becoming alarmingly low.

We require a two-pronged approach to address these issues: one in the short term, and one in the medium to long-term.

First, a clear path for adding Classics and/or Latin as a second subject must be made available to existing members of staff. We need courses which satisfy the GTCS’s requirement of 80 SCQF points (or for the GTCS to make Classics and Latin a special case by reducing the requirement to 60, thus turning any Open University module into a de facto conversion course), and these must be paid for by central government – god knows, local authorities do not have the money. Staff must be allowed time off to complete these courses, and be supported by schools to see them through. If we can do this, we will increase the pool of available registered teachers.

Secondly, in the longer term the Scottish government must invest in PGDE courses for Classical subjects. These will not turn a profit, and uptake will be small for many years, but this will be the price of equity, and a statement that state school pupils are as entitled to learn about Julius Caesar as their privately schooled peers.

Or as the Scottish government themselves put it:

Every. Child. And. Young. Person.

The. Same. Opportunity. To. Succeed.

It is not okay to foist all the responsibilities for saving these subjects onto enthusiastic classroom teachers. They have more than enough to be doing in their day-to-day work without also shouldering the financial, emotional, academic, and professional stress of achieving registration as a Classical Studies or Latin teacher.

Purely in terms of protecting ourselves as workers, teachers should be contacting their union representatives and beginning a dialogue. As the area convener I work with explained to me: “These concerns are not unique to Classics, but the complete absence of a teacher training route in Scotland does set it apart from most other subjects.” It is a special case. So, what can we do?

Firstly, I would ask that all classroom teachers raise these issues with their union’s Education Committee. In my case this is with the Educational Institute of Scotland. Once we have done this, we must propose a motion to the AGM to have it considered as a part of the union’s campaigning priorities.

· We need more support for one-person departments.

· We must overcome the precarity of contracts which do not reflect the work being done.

· We must increase and improve training and registration opportunities.

This is not the route I would want us to take, but without pressure from the unions, without making the case that these issues are in breach of the ethics of education held by the Scottish government, it is unlikely that policy-makers will take them seriously.

We must also act to protect ourselves as workers. If we do so, it is possible that the GTCS, the Scottish government and other policy makers will see these problems in the right light, and we can build on the small victories in Classical Studies courses, and begin to establish foundations for a sustainable long term for Classics in Scottish state schools.